During the Jacobean era in England, a time that spanned the reign of King James I from 1603 to 1625, society was structured by a rigid worldview that placed every element of existence within a hierarchical framework known as the Great Chain of Being. This philosophy, deeply rooted in medieval thought but still powerful in Jacobean times, shaped people’s understanding of the natural world, social class, religion, and even human emotions. It was more than a theory it was the lens through which life itself was interpreted, accepted, and justified.

Origins and Philosophical Foundations

Classical and Theological Roots

The concept of the Great Chain of Being originated from classical antiquity, particularly in the works of Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle. However, it was fully developed and adopted into Christian theology by medieval scholars such as Thomas Aquinas. In this hierarchical model, every element in the universe was seen as part of a divine order, arranged from the most spiritual and perfect down to the least spiritual and most material.

Structure of the Chain

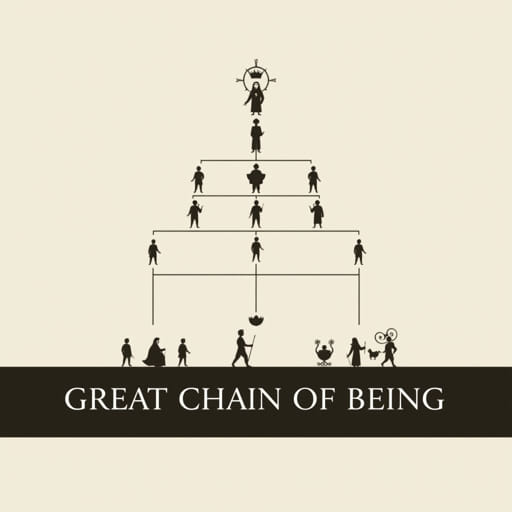

The structure of the Great Chain was typically as follows:

- God the ultimate and most perfect being

- Angels spiritual beings without physical form

- Humans the link between spiritual and material worlds

- Animals driven by instinct, lacking reason

- Plants living but not sentient

- Inanimate objects rocks, minerals, etc.

Within each category, there were further subdivisions. For example, among humans, monarchs were considered closer to the divine than peasants.

The Great Chain in the Jacobean Era

Social Hierarchy and Divine Order

In Jacobean England, the Great Chain of Being was reflected in the rigid social structure. At the top was the king, believed to be appointed by divine right. Below him were nobles, knights, merchants, and peasants. This hierarchy was considered natural and unchangeable, with everyone expected to accept their place in the chain.

Religious Reinforcement

The Church played a critical role in reinforcing the idea of the Great Chain. Sermons, religious texts, and official doctrine all supported the belief that the existing order was God’s will. To question one’s position was to question divine providence itself, which was not only heretical but socially disruptive.

Impacts on Literature and Art

Reflection in Jacobean Drama

The influence of the Great Chain of Being is evident in Jacobean literature, particularly in the works of William Shakespeare and his contemporaries. In plays such asKing LearandMacbeth, disruptions in the natural order such as rebellion, regicide, or betrayal lead to chaos and suffering, underscoring the belief that the cosmic hierarchy must be respected.

Symbolism and Allegory

Jacobean poets and playwrights often used animals, celestial bodies, and natural phenomena as symbols to express the hierarchical order. For example, the lion represented royal authority, while the sun symbolized the king. Allegories of harmony and disorder were central themes in works seeking to teach moral or political lessons through narrative.

Political Implications

Legitimizing Monarchical Authority

King James I himself was a firm believer in the divine right of kings, an ideology aligned closely with the Great Chain. He published works likeBasilikon DoronandThe True Law of Free Monarchies, which outlined the king’s role as God’s appointed ruler. In such a view, political dissent or rebellion was not just treasonous, but sinful.

Stability and Obedience

By maintaining belief in the Great Chain, rulers could ensure greater societal stability. People were taught that obedience to authority, even in suffering, was virtuous and rewarded by God. Any attempt to rise above one’s ordained status was seen as both dangerous and unnatural.

Scientific and Philosophical Tensions

Rising Humanism and Skepticism

Despite the dominance of the Great Chain worldview, the Jacobean era also witnessed the beginnings of change. The Scientific Revolution was beginning to challenge older models of the universe. Thinkers like Galileo and Francis Bacon introduced empirical methods that questioned the static nature of cosmic and earthly hierarchies.

Philosophical Contradictions

Some scholars and writers began to question the moral implications of a system that justified inequality and suffering. The idea that one’s social position was fixed and divinely ordained became harder to reconcile with emerging ideas of reason, individual rights, and social mobility.

The Decline of the Great Chain

Transition to the Enlightenment

By the end of the 17th century, the rigid worldview of the Great Chain began to lose influence. The Enlightenment emphasized rationality, equality, and secularism, which stood in stark contrast to the hierarchical, spiritual order of the Jacobean world. Nevertheless, the legacy of the Great Chain persisted in conservative thought and literature for generations.

Continued Symbolism

Even after its philosophical foundation was undermined, the imagery of the Great Chain of Being remained embedded in Western art and culture. It continued to be used as a metaphor for order, interconnectedness, and the dangers of overreaching one’s place in the universe.

Modern Interpretations

Historical Perspective

Today, historians view the Great Chain of Being as a reflection of its time a worldview shaped by religious authority, limited scientific understanding, and a need for societal order. It offers insight into how early modern Europeans understood their place in the cosmos and the moral structures that governed their lives.

Literary and Cultural Legacy

In literature, the Great Chain remains a valuable tool for analyzing character motivation, plot structure, and thematic depth. Its influence is evident in classical education and continues to shape discussions of hierarchy and order in historical contexts.

The Great Chain of Being during the Jacobean era was more than a philosophical concept it was the guiding principle behind society, politics, religion, and art. Though its influence has waned over the centuries, it remains a powerful symbol of the human desire to find order and meaning in the universe. By understanding this hierarchical worldview, we gain greater insight into the values and beliefs of early modern England and the structures that defined one of history’s most fascinating periods.