In the aftermath of World War II, cinema around the world entered a new phase of artistic exploration, often reflecting the shifting dynamics of society, including the role of gender. The intersection of gender and film genre in postwar cinemas became a powerful tool for expressing social anxieties, hopes, and cultural transitions. Whether through Hollywood noir, European melodramas, or Japanese jidaigeki, filmmakers started to question traditional gender roles while using genre conventions to explore emotional, psychological, and political depths. These films became mirrors of postwar identity, showing how genre structures could support or subvert gender representation.

Hollywood’s Gendered Genres in the Postwar Era

Film Noir and Masculinity Under Pressure

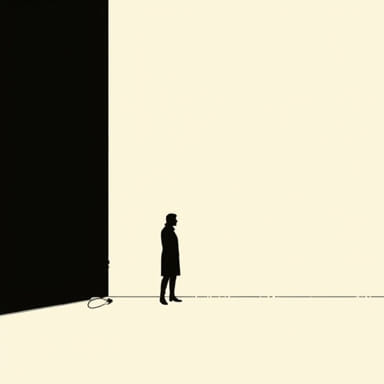

One of the most iconic genres to emerge from postwar American cinema was film noir. These dark, moody thrillers reflected the disillusionment and psychological instability of the time. Central to many noir films is a male protagonist often a detective, criminal, or drifter who struggles with moral ambiguity, violence, and distrust. His masculinity is often undercut by internal conflict or external manipulation.

Gender roles in film noir are deeply intertwined with genre tropes. The femme fatale character, for example, represents a threat to male power. She is independent, sexually assertive, and often the cause of the male lead’s downfall. Films like *Double Indemnity* and *The Postman Always Rings Twice* showcase women who challenge male authority, forcing audiences to reconsider the ideal of postwar masculinity as strong, rational, and dominant.

Melodrama and Women’s Emotional Labor

While noir centered on male anxiety, melodrama emerged as a space where female subjectivity took center stage. Often dismissed as women’s films, postwar melodramas dealt with domestic life, romantic conflict, and moral dilemmas through deeply emotional storytelling. Directors like Douglas Sirk crafted visually stunning films that addressed repression, desire, and sacrifice.

These films highlighted the constraints placed on women within marriage, motherhood, and society. Gendered genre tropes such as the devoted housewife or the suffering mother reflected real-life struggles while subtly criticizing patriarchal norms. Melodrama became a coded form of resistance, giving voice to women’s interior lives in a culture that often silenced them.

European Postwar Cinema and Gender Politics

Italian Neorealism and Working-Class Women

In Italy, neorealism emerged as a powerful cinematic response to the devastation of war. These films focused on everyday people, often using non-professional actors and real locations. Gender in neorealist cinema was grounded in survival, labor, and resilience. Female characters were often mothers or wives trying to support their families amid poverty and instability.

Films like *Rome, Open City* and *Bicycle Thieves* portrayed women not as passive figures, but as active participants in rebuilding society. Their roles extended beyond the domestic sphere, challenging gendered expectations. The genre’s documentary style and focus on realism added authenticity to its representation of gender dynamics in postwar society.

French Cinema: Existentialism and the Gendered Gaze

Postwar French cinema, especially the works leading into the New Wave, frequently explored philosophical questions through intimate personal stories. Directors such as Jean-Pierre Melville and later Jean-Luc Godard delved into existentialism, alienation, and gender identity.

Female characters in these films were often positioned as muses or enigmas. However, some filmmakers began to explore the female perspective more directly. The tension between male-centered storytelling and emerging female voices revealed a shift in gender representation. The genre conventions of romantic drama or psychological thriller became tools for unpacking identity and desire in a changing world.

Japanese Postwar Cinema and Gendered Tradition

Jidaigeki and the Role of Women

Japanese cinema after World War II witnessed a renaissance of traditional genres, particularly the jidaigeki, or period drama. These films, set in the Edo period, often portrayed samurai values and moral dilemmas. While largely focused on male honor and duty, some films included powerful female characters who challenged social order.

Directors like Kenji Mizoguchi brought a deeply gendered lens to historical narratives. In films such as *The Life of Oharu* and *Sansho the Bailiff*, Mizoguchi used genre elements to critique patriarchal oppression. His female protagonists suffered but also endured, revealing strength within vulnerability. Genre thus became a means to interrogate both gender and historical tradition.

Contemporary Settings and Modern Womanhood

Apart from historical films, modern-set Japanese dramas also reflected shifting gender dynamics. Directors like Yasujiro Ozu portrayed quiet family stories in which generational conflict and gender roles were central themes. Women in these films were caught between duty to family and a desire for independence, echoing broader societal tensions.

Ozu’s minimalist style emphasized emotional restraint and social expectation. Through subtle interactions and domestic rituals, he revealed how gender shaped daily life and interpersonal relationships. These dramas served as a commentary on modernization and the changing place of women in Japanese society.

Gender Subversion Through Genre Blending

Breaking Conventions in Global Cinema

As filmmakers gained more creative freedom in the 1950s and 1960s, some began to play with genre boundaries to explore gender in new ways. This blending often led to subversion of traditional roles and the creation of complex, layered characters.

- Western + Melodrama: Films like *Johnny Guitar* inverted typical Western tropes by placing a strong female protagonist at the center of a genre known for rugged masculinity.

- Science Fiction + Domestic Drama: Some sci-fi films used genre to examine female identity and reproductive control, laying the groundwork for feminist reinterpretations in later decades.

- Comedy + Gender Commentary: Postwar comedies often relied on gender confusion and role reversal for humor, but in doing so, they also highlighted the arbitrary nature of gender norms.

This kind of genre mixing allowed filmmakers to comment on gender without direct political statements, using storytelling itself as a method of critique and reflection.

In the years following World War II, cinema became a powerful space for negotiating gender roles and societal change. Whether through Hollywood noir, European realism, or Japanese historical epics, filmmakers used genre not only to entertain but to question deeply rooted beliefs about masculinity, femininity, power, and identity. The interplay of gender and genre in postwar cinemas reveals the medium’s capacity to reflect and reshape cultural narratives. By examining these films through both lenses, we gain a richer understanding of how art responds to history and how it helps define the future.